Should creativity be taught? The answer is yes (and it’s also no). Can creativity be taught? The answer is yes (and it’s also no). The reason for the dichotomy is that creativity isn’t a topic or a subject, it isn’t even a collection of subjects. You can’t have a lesson on creativity in a similar way in that you can’t have a lesson in isolation on seeing or looking at things or on memory and remembering things. You’d need to have something to look at or remember and a reason to focus on them. We can think of creativity in a similar way (I wish I could think of a better analogy though, but hopefully you’ll get my point): being creative is a way of being, a way of doing something, rather than a beginning and end in itself. We have to apply it to an endeavour, and apply and enhance it we should.

Let’s rephrase my opening questions: should we foster creativity? Yes. Can we foster creativity? Yes. Can we and should we do this in science teaching? Yes and yes.

SCIENCE IS NOT A SUBJECT

Let’s take a step back. Science isn’t a subject either. Science is a way of thinking in a way that some subjects such as French or Geography perhaps are not. Ok, I’m probably a bit wrong here, every subject has a way of thinking. History, for example, has a body of knowledge like science, but a different methodology that defines and creates that knowledge that is different to the scientific method but operates towards the same truth-seeking results. Every subject has skills that need to be developed and can then be applied in practice. It does seem to be the case though that ‘rote learning’ can work better in knowledge based subjects but not so well in science. Teach science by rote and we produce, at best, good science technicians, but not great scientists.

Science obviously has a large body of knowledge but if we just taught that and got kids to memorise it all, we’ve done nothing more than produced human data storage systems. They won’t be able to ‘do’ science, just regurgitate the facts produced by it. The scientific method is a truth seeking methodology, a tool, and like any tool, it can be wielded by a better craftsperson for better results. Just having a chisel and knowing the rules for its use doesn’t make you a sculptor. There is something else needed for great art just as there is something else needed for great science. In both cases it’s the same thing: practical application, practice and creativity.

So science too must be taught and practiced with practical application and with creativity to enhance both the learning and the application of it.

But how?

What follows is my opinion bases on a decade of application, adoption, adapting and improvements to find what works and what doesn’t. It’s led me to some great and surprising results.

The first thing to consider is to create an environment conducive to creativity and creative thinking. There is the physical as well as the psychological environment to look at.

PHYSICAL SPACE

I like to make my classroom/lab as relevant as possible to the task in hand. It should be somewhat comfortable to be in for at least an hour in terms of how students are seated, spaced out enough to have clear sight and hearing of what is needed with areas to work safely individually or in groups with the variety of equipment required. I like the room to look welcoming, be scientific but not clinical. I like to have interesting and useful posters and display equipment that help create a collaborative space of belonging. A favourite memory of mine is a year 10 girl walking in and saying (although not to me) “I love this room!”. It should have a uniqueness and be both exciting and comforting to be there.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

Then there is the psychological space. What we need in our classrooms is what is known as psychological safety. This is the feeling of trust that a child has that they are able to ask questions, offer answers, to succeed and to fail without judgement of their character, without embarrassment or ridicule from the teacher or from their peers. I can’t stress this enough for a science teaching space: students have to feel safe enough to fail, to be wrong. This is the only way learning happens. It’s the key to the scientific method itself. It’s the key to growth and it’s the keys to creativity.

My most successful way of inducing this psychological safety is to embrace the ethos myself and make it visible to all. I too must be allowed to fail and must own that failure. So, if I get anything wrong, say a spelling, some grammar, the date, whatever, large or small, I want the students to be able to point that failure out. It doesn’t take long for a class to realise that if they spot an error on my part they get a sweet (a small lolly or something to consume later). The result? They watch me like hawks! They question everything. What attitude could be better for a science learning environment? This simple idea fosters an inquiry based learning environment. It allows their growth mindset to develop.

Richard Feynman said “I’d prefer to have questions that can’t be answered than have answers that can’t be questioned” (that too is a poster on my wall). We want questions from our students, no mater how simple or preposterous. They need to feel safe that everything can and should be questioned. Where possible we want to be asking them open ended questions. We want to be asking questions that need thought, that may have multiple answers. We need our students to say “I don’t know, but is it this?…” Rather than avoidance and silence or the “I don’t know” to be the end rather than the beginning of “so I’ll find out”. I’d rather have a guess and hypothesis than nothing at all. That again, is the scientific method in play. I’d rather they were wrong and then build on that answer than being afraid to fail and never even try. Creativity is all about not being afraid to fail and thus discovering something new. But we need to feel absolutely safe to be able to do this and we need to follow up with positive, constructive feedback throughout.

DON’T DO PRACTICALS…

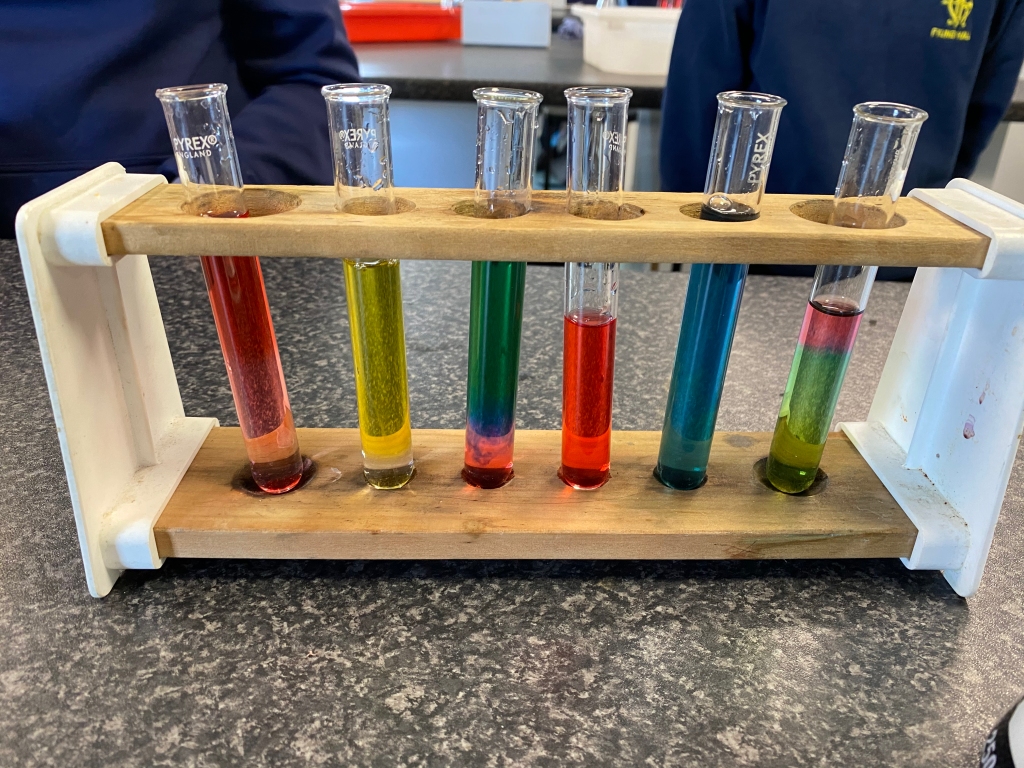

An atmosphere of diverse approaches the students can take to complete a task can be instilled by using diverse approaches to how information, tasks and challenges are put across to them. Have open ended projects that have multiple ways to seek the solution. Multiple solutions are so much better than tasks with zero sum game single path answers. This is why language too is important. I refer to any practical task we perform as ‘an experiment’ never ‘a practical.’ The default in curricular and in most schools is to call them all ‘practicals’. The teacher announces “today we are doing a practical”. They might as well announce “today we are going to mess about”. Do this and we’ll create a body of students who just want wizzes and bangs, forever demanding explosions and sparks. They will become busy fools who just want idle play and be entertained with no desire to learn. An ‘experiment’, on the other hand, demands a method. It demands a hypothesis. It seeks to find something out. A ‘practical’ isn’t even as noble as a cookery lesson where a recipe is followed – at least then you have a cake. Do a ‘practical’ and you have filled your time by using your hands, nice, but almost certainly useless. Labelling everything as an experiment sets up inquiry and a mystery. It sets up the process of discovery.

COLLABORATION

At the end of a GCSE or A level course there is the exam which of course is taken individually and in silence. But learning works best when there is collaboration and discussion. In real life and in almost all avenues of employment, teamwork and discussion are the main routines for getting things done. We need to teach these skills too. Being able to share ideas is highly motivational for an individual. Finding shared ideas and solutions is rewarding. Being able to learn how to put your ideas across, teach others what you know, cope with diverse opinions and how to change your mind when new evidence arrives are all vital skills that also aid learning. They need to be taught every bit as much as exam techniques. Allowing some autonomy where possible, either as individuals or as small groups by giving choice in how something is done or what is done. This also empowers students and increases their self worth and the value they place on their ideas.

CELEBRATE THE JOURNEY NOT JUST THE DESTINATION

As educators we often celebrate results and end-goal achievements. We should also be looking at celebrating journeys, processes, attempts and accomplishments along the way. We can reward how students went about something (even if the end result was off the mark). We can display students work, along with work in progress, or the pathway towards final piece. We can give student choices and autonomy over what should or could be displayed. We can design tasks with that goal in mind to deliberately enhance their science communication skills by asking them to present their ideas in person, in groups or as a piece of work for display.

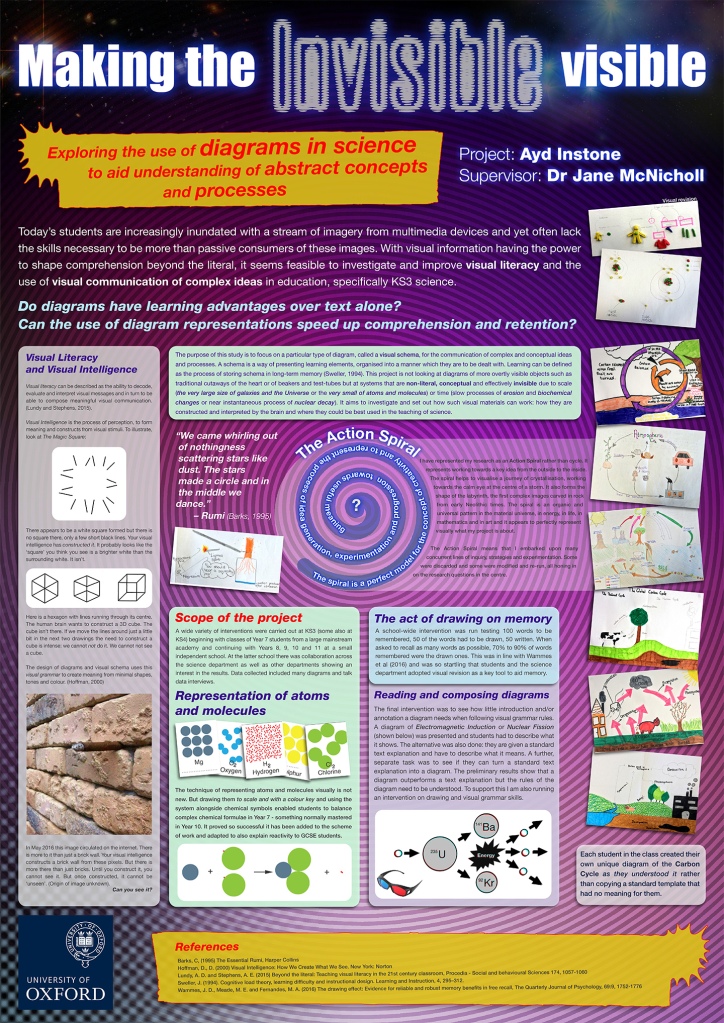

INFOGRAPHICS

Never, ever ask students to design a poster. A poster is an advert for a village fete or to promote a new packet of crisps. Ask for a poster and that is all they will ever create, spending more time on the title than ever thinking about the subject in hand. Instead, ask them to create an Infographic. Yes, it’s a poster, but it has to by definition, communicate an idea in works and pictures. Search the internet for ‘infographic of…’ a certain thing and you’ll be surprised how useful the concept is.

The use of technology can be a highly creative force too. But it can also stagnate minds. Simply asking for report on a research topic will get you badly cut-and-pasted Wikipedia scraps. Ask for an essay and you will now get an A grade essay created instantly by ChatGTP. Both of these methods have no learning value. Again, we need to teach our students how to research which is also a creative process. Referencing websites appropriately and using Artificial Intelligence tools are very useful if used constructively to support a greater process.

CONNECTIONS

If I tried to define what learning is, or what creativity actually is I’d end up with the same simple definition which is this: the ability to notice patterns and to remake them into new structures. Both learning and creativity are about making connections, Both literally, by connecting neutrons in the brain, and figuratively by putting concepts and ideas together in new ways. To that end we should foster connections wherever we can.

I have a massive poster on my lab wall that has icons representing 150 scientists from ancient Greece to the present day. I refer to this tapestry of history during lessons, telling the human stories of those involved in discoveries. The students can see who was around in which era, how close or far apart certain discoveries and inventions were, linking people, events, time and objects together in new ways.

We should be making connections to today too – to real world applications, current career opportunities, the relevance of a particular obscure sounding part of the syllabus to the technology you depend on every day, to the world around us, the threats we face, the advancements we need. Science doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is multidisciplinary and it should be seen as such. We should be promoting links with other school subjects as well as the more obscure applications in the wider world – the symbiotic relationship between all knowledge and human endeavour.

JUDGE EVENTS NOT PEOPLE

Finally, let me end by telling you about the most damning obstacle to both fostering creativity and student achievement at school in general. It’s the idea of self-restriction by labelling, often self-labelling, sometimes school labelling by default. It’s the idea that ‘I’m not creative because I’m good at maths/science/whatever’. You hear adults say it all the time, ‘I’m just not creative’. The opposite is just as damning, ‘I’m good at art so I can’t be good as science’. It’s a result of the siloing, partitioning, categorising and pathways that schools do so well without realising the unconscious implications that they’ve inadvertently labelled everyone as this or that. It is so prevalent that we have to constantly check our language to make sure we’re saying “you have achieved a grade 6” and not “you are grade 6” just as we need to say “you have got this wrong/you have made a mistake” and not “you are wrong/you are a mistake”.

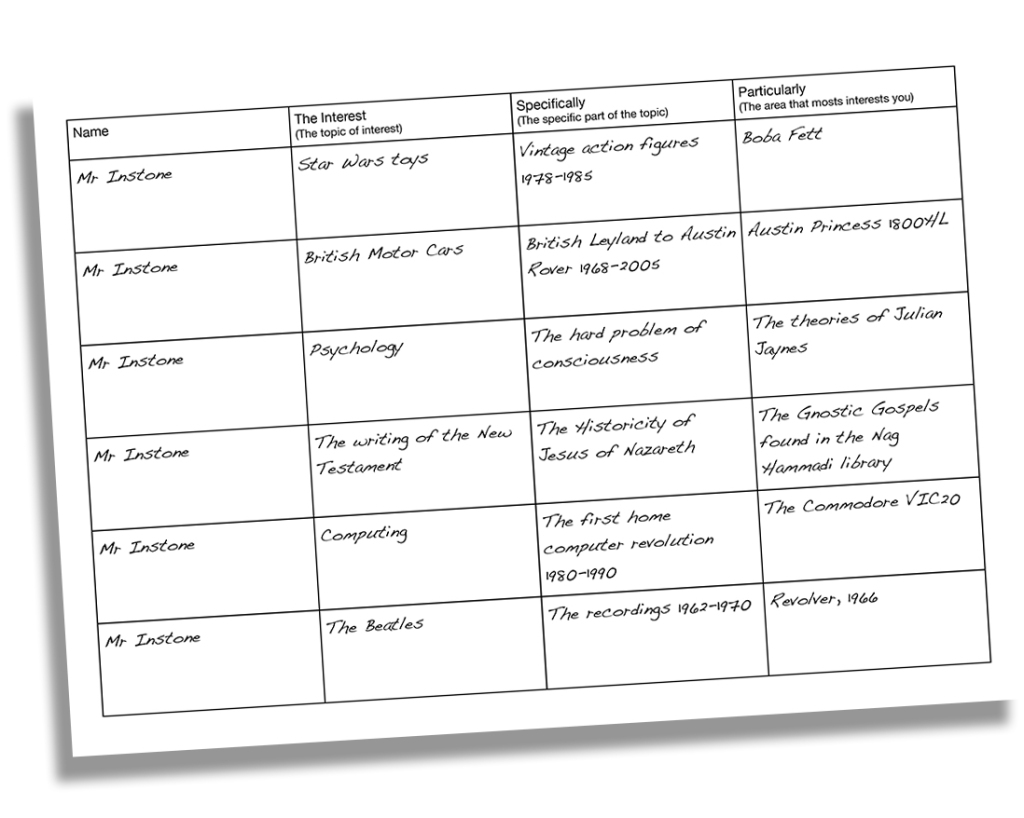

We need to make sure our language and definitions are accurate and open: we are ALL capable of being creative and being more creative – if we know how, and choose to do so. Like everything in life – you become what you do the most. Creativity is not something you are, it’s something you do, an action, a behaviour. Remember that fostering creativity is an ongoing process, it’s essential to adapt and refine any and all of these approaches and ideas based on your specific needs and the interests of your students.

Good luck.